This article was updated in 2021.

Section 116 of Canada’s Income Tax Act covers what non-residents must do when disposing of Taxable Canadian Property. This article explains tax law in Canada and possible estate planning issues as they relate to section 116.

Application to the estates context

Often, an estate will both hold real estate and have beneficiaries living in the US. In this context a question arises whether a section 116 clearance certificate is required upon the sale of real estate by the estate and distribution of proceeds to a United States beneficiary. This article will argue that if certain conditions are met there is a defensible position that no clearance certificate is required.

Overview of Section 116 application

Section 116 of the Income Tax Act (the ITA) sets out the reporting and withholding obligations for non-residents that dispose of Taxable Canadian Property (TCP). The purpose of this provision is to ensure that non-resident vendors do not shirk their Canadian tax obligations. The ITA provides that a purchaser must withhold a portion of the purchase price (either 25 or 50 per cent) when a non-resident vendor disposes of TCP, unless a clearance certificate is issued. If the purchaser fails to withhold and a clearance certificate is not issued, the purchaser could be liable for the amount that should have been withheld.

In many cases, it is not clear whether withholding is required. Generally, where it is uncertain that withholding is required, purchasers exercise caution and withhold. This cautious approach is burdensome as it usually takes a few months for the seller to obtain a clearance certificate. As a result, it would be of benefit to know with certainty whether withholding pursuant to section 116 is required. This article will examine a situation where a US resident beneficiary disposes of its capital interest in a Canadian resident trust (Trust) that held but does not presently hold TCP.

We argue that the Convention Between Canada and the United States of America with Respect to Taxes on Income and on Capital (Convention) effectively overrides section 116 and does not require reporting of a disposition of a capital interest in a Trust. This leads us to believe that the non-resident person does not need to apply for a clearance certificate and remit section 116 withholding tax to the Canada Revenue Agency (the CRA). This position assumes that the Trust is not a Quebec trust and that the US resident person is not related to the trustee of the Trust.

Examining the transaction at issue

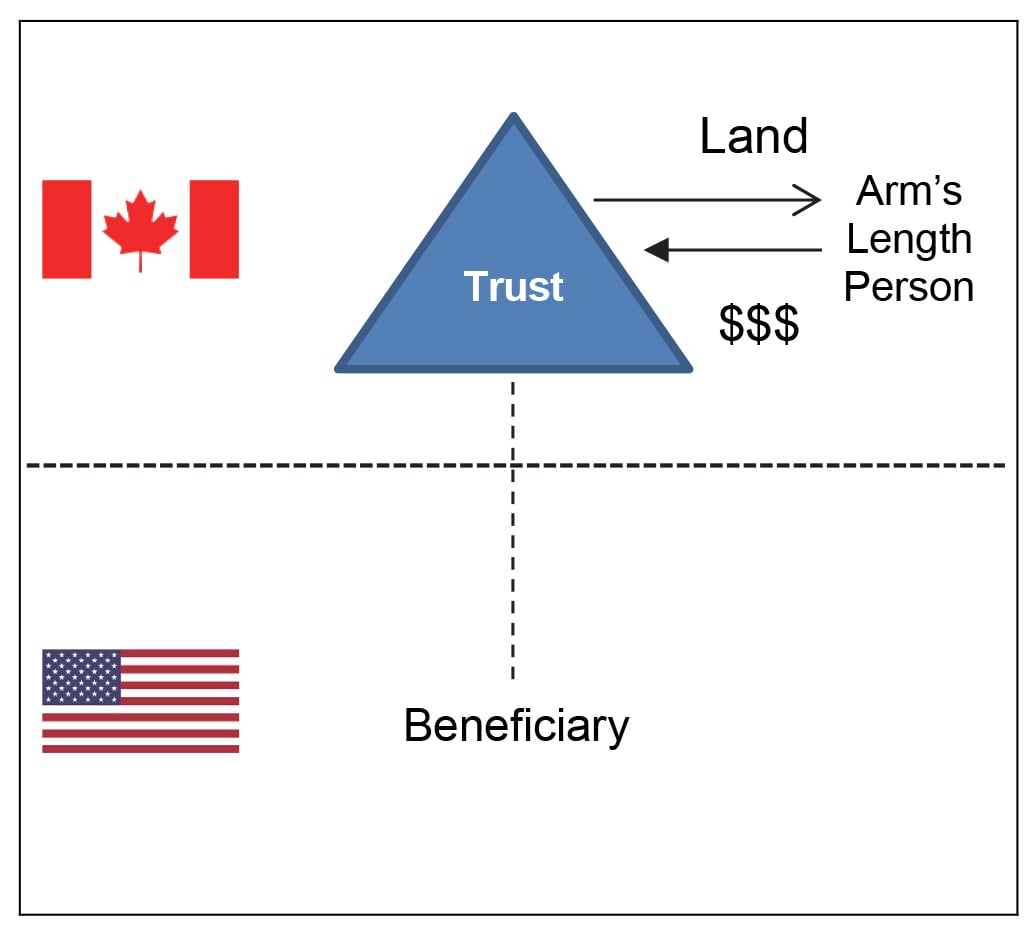

Consider the situation of a Trust (which generally includes an estate for the purposes of tax law) whose sole asset is Canadian-situs real property that appreciated in value. The Trust disposes of this property to an arm's length buyer. As a result, the Trust realizes a capital gain. This capital gain can either be taxed in the Trust or, if an election is made, the capital gain could be flowed out to the U.S. resident beneficiary and taxed in the hands of that beneficiary.

Diagram 1 — Disposition of Land by a Trust

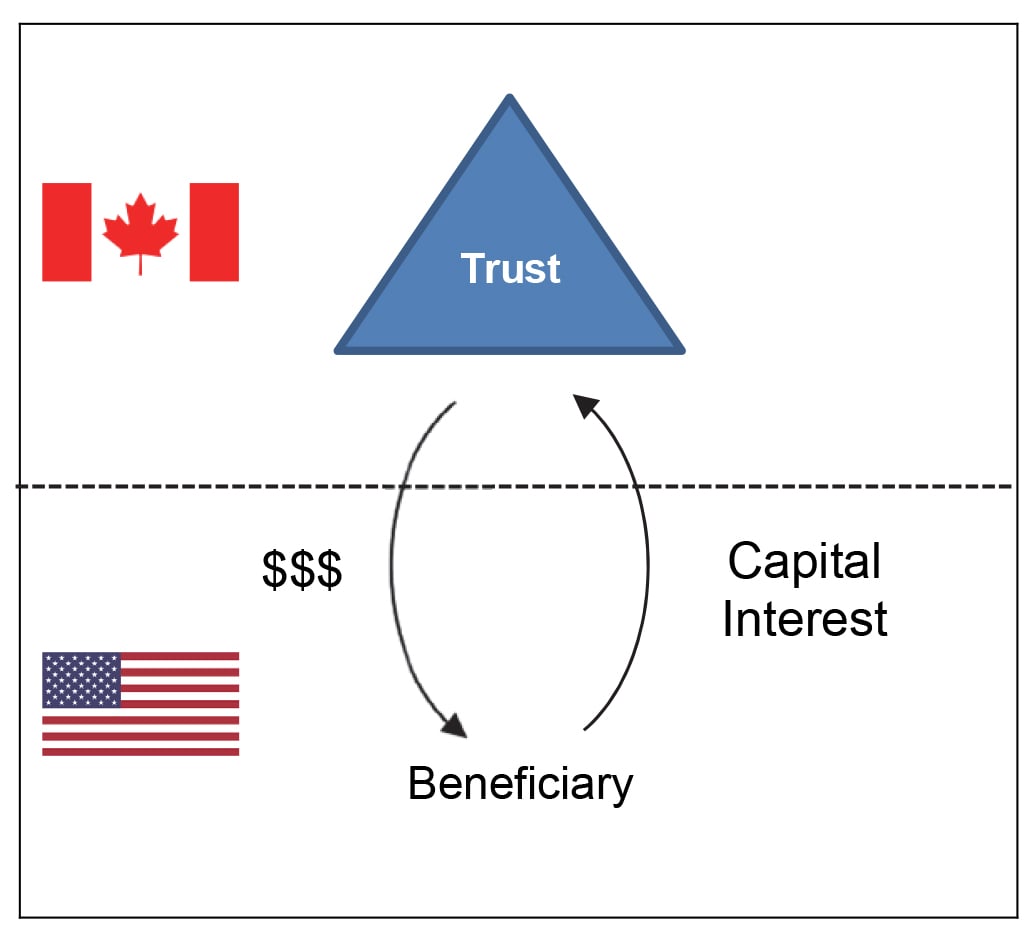

Where the Trust chooses to pay tax on the capital gain instead of flowing it out to the beneficiary, the remaining proceeds of the sale become the Trust's capital. Subsequently, the Trust can distribute funds held in the Trust to the beneficiary in exchange for beneficiary's capital interest in the trust.

Diagram 2 – Distribution of Capital by a Trust

The purpose of section 116 is to prevent a situation where a non-resident sells Canadian real property without paying the required Canadian capital gains tax. The distribution of capital out of a Trust is not subject to capital gains tax. Since there is no tax payable by a non-resident in this transaction, there is no reason why section 116 reporting and withholding obligations should apply. A cursory reading of section 116 would, however, suggest that they do.

The following sections examine why many believe section 116 applies and explores an exemption that can arguably take one out from the purview of section 116.

Why many believe Section 116 catches distribution of capital from a trust

The reporting and withholding obligations under section 116 apply to an interest in the Trust that is TCP. Subsection 248(1) of the ITA indicates that an interest in a Trust qualifies as TCP when more than 50 per cent of its fair market value was derived, directly or indirectly, from Canadian real property in the 60 months prior to its disposition. If the Trust does not meet this threshold, the U.S. resident beneficiary has no section 116 reporting and withholding obligations upon disposition of its capital interest in the Trust. A Trust whose fair market value is solely derived from real estate in the previous 60 months would be caught by the TCP definition. This definition catches the distributions of capital from a Trust that sold real estate and distributed the proceeds to non-resident beneficiaries within 60 months of the sale.

When there is a belief that a transaction is caught by section 116, the normal course of action is for t he vendor to report the transaction to the CRA and obtain a clearance certificate. Until a clearance certificate is obtained, the purchaser must withhold and remit a portion of the total proceeds to the CRA as a pre-payment of tax that will be owed by the non-resident vendor. Obtaining a clearance certificate can be a lengthy process. Thus, both parties benefit if section 116 obligations do not apply as the disposition process can proceed faster and funds are not unnecessarily tied up.

There are some exemptions from section 116 obligations. Section 116 obligations can be avoided if the property that is being disposed of meets the definition of "excluded property" in subsection 116(6) of the ITA.

Examining the "excluded property" exemption

The "excluded property" exemption is of potential benefit because the definition of "excluded property" includes "treaty-exempt property." "Treaty-exempt property," where the U.S. resident beneficiary is unrelated to the trustee of the Trust, is defined as "treaty-protected property." In essence, if the capital interest in a Trust meets the definition of "treaty-protected property," section 116 obligations are not applicable.

"Treaty-protected property" is defined in subsection 248(1) of the ITA as "property any income or gain from the disposition of which by the taxpayer at that time would, because of a tax treaty with another country, be exempt from tax under Part I" of the ITA. This definition requires us to look to the Convention to determine whether the sale of an interest of the Trust is exempt from Part I tax.

Whether the proceeds from the disposition of a US resident's capital interest in a Trust are "treaty-protected" by the Convention depends on the interpretation of the provisions in Article XIII. Article XIII states that gains derived by a US resident from the alienation of real property situated in Canada may be taxed in Canada. Article XIII(3)(b)(iii) then defines "real property situated in Canada" as an interest in a Trust, "the value of which is derived principally from real property situated in Canada".

Interpreting value "derived principally" from real property: Convention trumps the ITA

In our scenario, the Trust disposes of its real property before the U.S. resident disposes of its capital interest in the Trust. Most of the value of the capital interest, however, will have been derived from the sale of real estate. This raises the question of whether its value is still derived principally from real property situated in Canada and therefore subject to tax in Canada pursuant to the Convention, or if it is exempt from tax in Canada.

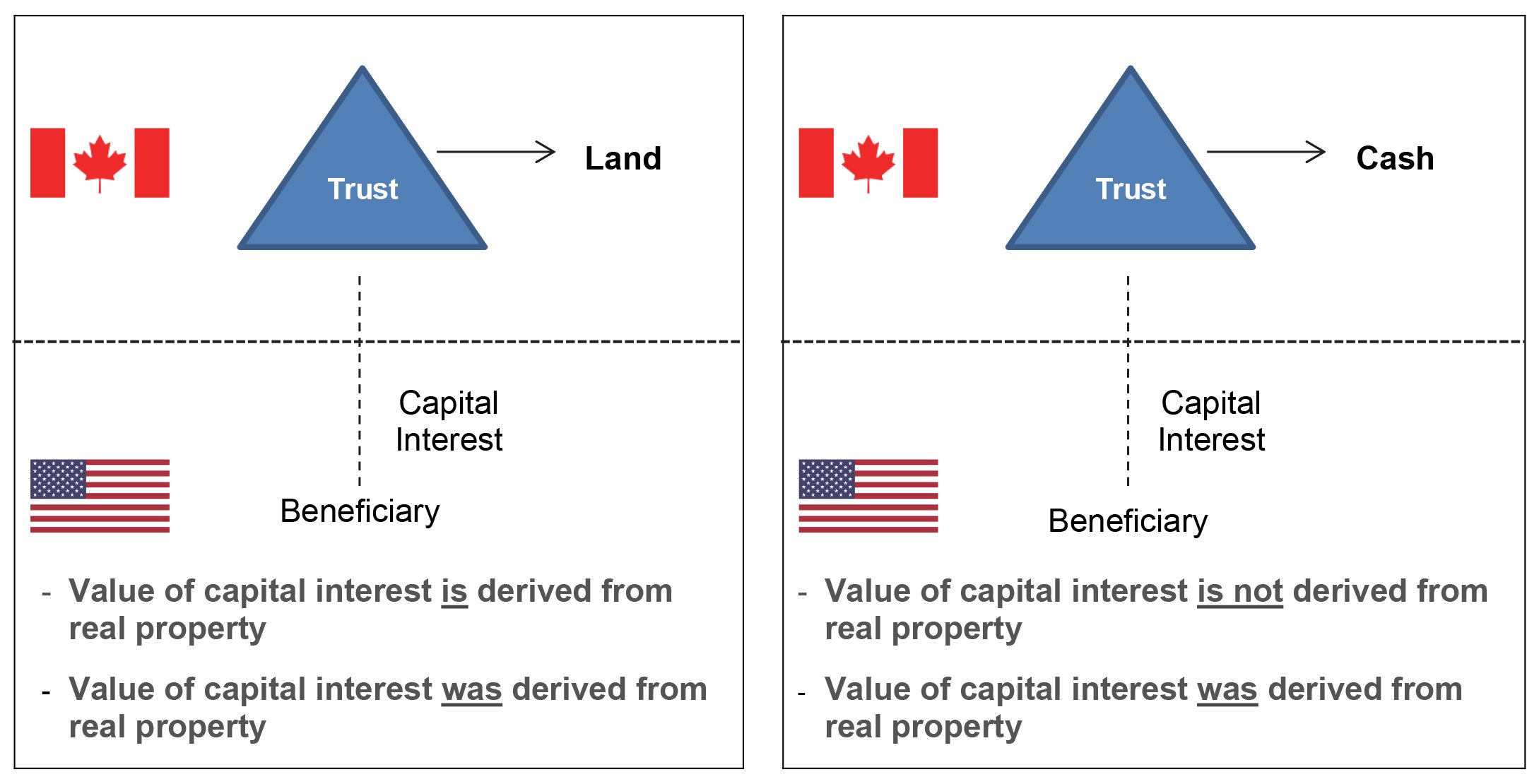

The point-in-time language used in the Convention captures an interest in a Trust whose value is derived from Canadian real property. The Convention does not appear to require retroactive tracing of the source of funds and is only concerned with the assets held in a Trust when the beneficiary disposes of its interest in the Trust. Therefore, if the Trust holds Canadian-sites real property at the time the U.S. beneficiary disposes of its capital interest, the Convention permits the property to be taxed in Canada and section 116 withholding and reporting obligations would apply. If, however, the land is sold and subsequently the beneficiary disposes of the capital interest in the Trust, the Convention does not expressly permit property to be taxed in Canada as the value of the capital interest in the trust is no longer derived from real property. As a result, section 116 obligations do not seem to apply.

Diagram 3 — Before Sale Of Land and Diagram 4 — After Sale Of Land

In contrast, the ITA defines TCP as "an interest in a trust ... if, at any particular time during the 60-month period that ends at that time, more than 50 per cent of the fair market value of the share or interest... was derived directly or indirectly from Canadian real property." The ITA, therefore, appears to be concerned with the source of the Trust funds for a 60-month period before the disposition of the Trust interest, and not any time before that. The Convention seems to reject this look back period and provides that tax may be payable to Canada if the Trust, at the time of the disposition, derives its value from Canadian real property.

The interpretation that the Convention is narrower than the ITA is further supported by the fact that the Convention does not adopt some other broader language of the ITA. The target of the Convention is a Trust whose value is derived principally from Canadian real property, while the subject of the parallel ITA provisions is a Trust whose value was derived "directly or indirectly " from Canadian real property. The Supreme Court of Canada has accepted the dictionary definition of "indirectly" to mean "circuitous or roundabout."1 This wording clearly signals a requirement to look behind the current contents of a Trust and to trace the historical source of its value. Due to this wording, if there is a "roundabout" link between the value of the Trust and Canadian real property, the Trust is subject to section 116 obligations.

In summary, not using the words "was derived" and "indirectly" in the Convention must have been intentional. Exclusion of these words suggests that the Convention was not designed to capture and tax, in Canada, a disposition of an interest in a Trust that previously held real property but no longer holds real property.

CRA's view of the world

Despite the above, the CRA has stated that it may be beneficial to a purchaser to require a clearance certificate even if the purchaser believes that the vendor qualifies for treaty relief under the Convention.2 It is worth noting that, where the purchaser has made a good-faith attempt to determine if the property is treaty-protected and has notified the CRA of the transaction, the purchaser will generally be shielded from liability if an audit later reveals that the property is not treaty-protected.3

Conclusion

If a Trust sells Canadian real property prior to a US resident disposing of its capital interest in the Trust, the proceeds that the US resident receives from the disposition could be considered “treaty-protected property” because they are not, at the time of disposition, principally derived from Canadian real property. This transaction would therefore be exempt from tax under Part I of the ITA. As a result, the US resident may not be required to obtain a clearance certificate and the transaction would not be subject to Section 116 reporting and withholding obligations.

BLG's tax lawyers and estate lawyers are available to help with your section 116 clearance certificates and other trust and estate-related needs. Reach out to your BLG lawyer or any of the contacts below for assistance.

1 Army and Navy Department Stores Ltd v MNR, [1953] CTC 293, 53 DTC 1185, [1953] 2 SCR 496.

2 Technical Interpretation 2008-0289051E5, "Section 116 and treaty protected property" (Jan. 4, 2011).

3 Ibid at 1.