Introduction

Carbon tax. Carbon pricing. Carbon markets. Emissions trading schemes. Carbon leakage (it’s a thing). Border Carbon adjustments. Words and concepts that a generation ago would have meant little to non-experts are now the focus of national political conversations.

We do not propose to wade into the politics or take sides in the current debate about the most effective measures to tackle climate change caused by human activity (anthropogenic climate change, or ACC). It’s important, however, to familiarize ourselves with the concepts.

After all, slogans have consequences, nationally and internationally; for our pocketbooks as well as our exports – and export-dependent jobs; in domestic policy terms as well as in our trading and economic relations with partners, allies, and adversaries.

This paper starts with explaining the basic concepts at play in the climate change policy debate. It then discusses an increasingly popular trade policy instrument to ensure global capture of carbon externalities (one of the concepts to be described) and carbon “leakage”. We will then explain how these measures affect, or could affect, Canadian exports depending on our choice of climate change policy.

We hope, in this way, to shed light rather than heat on an important national policy debate.

What is this all about?

The carbon externality

In simple, and perhaps simplistic, terms, increasing amounts of “greenhouse gasses” (GHGs) are changing the Earth’s climate – and, in the process, transforming the human habitat.

First identified as a potential source of “considerable” climate effect “in a few centuries” in 1912, carbon dioxide (CO2) generated by human activity (mostly in the form of fossil fuel consumption) is the most important of these GHGs (though not necessarily, in similar volume terms, the most harmful – a discussion for a different paper). Managing – and, over time, reducing – our output of GHGs is essential in the literal sense of the word: if we do not act, we may end up destroying ourselves. (The planet, of course, will go on its merry way – as in fact it did when it was a lifeless ball of fire for 500 million years.)

In this particular sense, like every other life-giving substance, above a certain concentration, atmospheric CO2 becomes a pollutant. But because it is ubiquitous, unlike other pollutants – say, an oil spill – CO2 is not easy to clean up. Efforts at “carbon capture and sequestration” continue, but the scale of the output simply overwhelms our capacity to put away excess CO2.1

In any event, the way to tackle a pollutant is to reduce its emissions, not to clean it up afterwards.

There are two further complicating factors.

The first is that, in the case of GHGs, for historical, economic, and political reasons, the clean up costs and the costs of the environmental harm caused by the pollutants have predominantly been left to society at large.

This is a classic example of a global “externality”.

In a perfect market, the price of a good would include environmental impacts along its life cycle. In this way, market engagement with the good would capture the direct and direct effects of its production and consumption. But market structures do not ‘price’ a good in a way that captures all costs, including environmental impacts. This is how using an improperly priced good gives rise to economic externalities: negative consequences of private use that someone else — usually society as a whole — ends up paying for. Modern regulatory frameworks seek to capture negative externalities as much as possible, using price signals and other measures. Carbon pricing is one type of corrective measure. Taxes or limitations on using environmentally harmful goods are another.

Failure to price for externalities remains global and endemic.2

The second is that we have already surpassed most of the critical “redlines” in the Climate Change Challenge. At this point, the best we can hope for is – at some point in the future – a “net-zero emissions” balance of economic activity. This does not mean ending fossil fuel use, but rather, ensuring that in the global balance of our energy consumption and economic output, we put as much CO2 into Earth’s atmosphere as is taken out, mostly through natural phenomena.

How do we do that?

Pricing carbon

As it happens, we have a lot of experience – gained since the advent of the environmental movement in the early 1970s – in managing pollution.

Broadly speaking, there are three ways of controlling or reducing pollution:

- we can price it in the market through a “tax”;

- we can price it through a specialised “market” mechanism; or

- we can regulate it.

These can work separately or in tandem; at the same level of effectiveness, each has its own attendant costs and benefits.

In a carbon tax/direct carbon pricing environment, the “tax” represents the “externality” assessed to exist. By attaching the cost of the externality to the price of the good, a price signal is sent to the consumer:

“This is the real cost of the good you are buying. You can choose to buy this good that is not environmentally sound (and therefore has a pollution tax attached to it), or another good or service that has a lower carbon footprint, and therefore lower carbon tax, and therefore lower price.”

Inevitably, some goods end up costing more than others – that’s the whole point of the market signalling – but the ultimate choice is left to the consumer; consumer behaviour, it is surmised, in the long run, will favour lower carbon footprint goods than other goods. And this will, in turn, result in lower carbon emissions.

“Emissions trading schemes” (ETSs) are a form of market mechanism realization, though considerably more complex in operation than a simple tax. At least initially, ETSs could operate at a lower impact to the consumer because of “initial allocations”.

Under an ETS, entities subject to the scheme are allotted a certain number of permits or allowances that set a limit to the amount of pollutants—in this case, greenhouse gases—they are permitted to emit. Where an entity needs to increase that limit, it may enter the market and purchase additional allowances (i.e., credits). An ETS effectively enables certain emitting entities to purchase the right to pollute, while rewarding others for reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. The aim is to have those entities that can reduce emissions most cheaply do so, with the ultimate objective being an overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions at the lowest cost to society.

Typically, an ETS functions by first establishing an overall limit on pollution levels, or the total amount of clean air emitters are permitted to consume. Governments set this limit as a baseline to achieve a targeted reduction in emissions.3

In a regulated framework, each consumer or producer is told how much of the pollutant they may release into the environment. This is the case for most noxious substances.

The Canadian landscape

Canada’s federal carbon tax landscape includes a combination of a traditional tax,4 market mechanisms, and a regulated framework applicable under parallel and mutually exclusive regimes contained in the federal Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA).

The fuel charge: sending the wrong signals?

The federal fuel charge, which is commonly referred to as a consumption-based carbon tax, is imposed at the first delivery of a carbon intensive product itself and is calculated on projected emissions released during combustion, effectively taxing the carbon intensive inputs rather than direct emissions produced. The fuel charge is subsequently absorbed into the cost base of goods and services supplied further down a supply chain. While this achieves the overall objective of a carbon tax in that it increases the cost of goods and services by internalizing the cost of carbon, the “tax” itself is paid long before the impacted goods and services are purchased by end consumers. This means that the price signal intended to inform, and indeed alter, consumer behaviour often lacks transparency.

From a purely economic standpoint, transparency may seem unimportant. However, as informed consumers may be willing to, and indeed do, pay a premium for low carbon or sustainable products and services, the price signal may actually push even well-intentioned consumers in the wrong direction. This happens when consumers favour higher priced goods under the misapprehension of quality or superiority from an ESG perspective, whereas the higher price actually reflects increased cost due to the imposition of the fuel charge higher up in the supply chain.

This is all before other market actors may further obfuscate the intended price signal through adjusting retail profit margins or adding fuel surcharges and the like.

Add on general inflationary pressures on the cost of living ubiquitous in any discussion of consumer behaviour in recent years, and one can see that the intended economic efficiently of a carbon tax’s ability to internalize the cost of externalities and inform consumer choice can prove difficult in execution.

Industrial emitters

In contrast to the fuel charge, the GGPPA also includes a parallel Out-put Based Pricing Solution (OBPS) regime for industrial emitters.

In simple terms, the OBPS regime allows registered emitters to purchase carbon intensive inputs exempt from fuel charge (i.e., no consumption-based carbon tax), but are instead required to account for actual emissions produced by a covered facility. Put differently, the OBPS exempts the price of carbon on inputs in favour of pricing outputs to pursue a reduction of actual emissions in the most economically efficient means through a combination of market mechanisms and regulatory pressure.

Key to the functioning of the OBPS regime is the establishment of an emissions benchmark, which forms the regulatory limit on carbon emissions for a given facility before the imposition of costs. If emissions meet the emissions benchmark, no compliance action is required. However, when emissions exceed the benchmark, the registered emitter must pay for each tonne of CO2 above the benchmark based on the prevailing price per tonne of CO2 or retire emissions credits. In contrast, when emissions are below the benchmark, the registered emitter is able to produce transferable emissions credits that can be retained for retirement against future excess emissions or can be sold in the open market.

From a regulatory perspective, OBPS regimes will generally mandate an emission reduction target from an initial benchmark and/or increase in the cost of exceeding the targeted emission benchmark by increasing the per tonne rate of tax. From a market mechanism perspective, the transferrable nature of these credits incentivizes registered emitters to pursue technologies that reduce emissions beyond their targeted emissions benchmark in order to generate credits that can be sold at a profit to mature industries that may encounter technological or cost ceilings to their ability to decarbonize operation.

A federal, or federalism, backstop

If the nuance of the parallel federal carbon regimes under the GPPPA was not complicated enough, Canada has an added element of being a geographically diverse federation subject to constitutional limitations on the powers of each level of government. Specifically, the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments under the Constitution Act 1867 and the propensity for tensions between their respective heads of power – it would be an understatement to say provinces are weary of federal forays into areas of provincial jurisdiction. Let’s not forget that the GGPPA itself was the subject of a reference case to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2021 after challenges from multiple provincial governments.

To navigate this complexity, the GGPPA was established as a “backstop” to set a minimum price on carbon across Canada, leaving room for provinces to enact their own carbon tax regimes that meet or exceed the federal benchmark price on both the consumption-based tax and the industrial emitter side. An opportunity that several provinces have pursed, in whole or in part. While provincial specific regimes are beyond the scope of this analysis, the great Canadian regulatory laboratory has developed domestic experience within Canada in assessing equivalency and or acceptability of various approaches to pricing carbon to ensure alignment of carbon taxation within Canada that avoid potential interprovincial carbon leakage.

For example, Québec’s adoption of a Cap-and-Trade System, under which emission credits are linked to other jurisdictions outside of Canada, has been deemed sufficiently robust to not require intervention of a federal backstop. Whereas Manitoba’s made in Manitoba Climate and Green Plan was not considered sufficient when proposed, leading Manitoba to become a listed province for purposes of the GGPPA.

Carbon pricing and international trade

It seems then that despite Canada’s geographic diversity and constitutional limitations on power, the combination of federal paramountcy and the ability to impose a backstop across the entire country can mitigate the major risk of interprovincial carbon leakage. So far, so good.

But taking this to the international level, what if a country prices carbon and its trading partners do not?

This produces a competitive advantage for imported goods from origins without similar carbon pricing regimes. The result being that there is an increase of carbon “leakage”, i.e. a relocation of production to an export country that have less stringent climate policies and carbon-pricing schemes in place.

Enter Border Carbon Adjustments (BCA) (also know, in the EU framework, as Carbon Border Adjustment Measures or CBAM – not to be confused with a sound effect in a 1960s Batman episode).

A BCA is a carbon pricing mechanism on goods that cross the border. From an economic perspective, it seeks to ensure that where a good that is not subject to effective carbon pricing crosses the border, measures at the border remove any competitive advantage that unpriced imports might have relative to priced domestic goods.

Properly constructed, a BCA levies a price on the imported goods equal to the domestic carbon charge for certain goods, particularly in emissions-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) sectors minus any carbon charges already paid on the good. (Otherwise, there would be a double taxation of the carbon.)

BCAs may take the form of an import charge a rebate on exports.5

- An Import Charge on imported goods reflects the difference in the carbon price associated with that particular good between the two countries (i.e. the origin country vs. import country).

- An Export Rebate levels the playing field whereby domestic goods originally exposed to domestic carbon pricing for their emissions are provided with a difference in pricing when they export their goods to countries with differing carbon pricing schemes.

Bank of Canada statistics reveal that Canada’s tariff rates imposed on imports are greater than the United States, yet less than Europe’s rates. The greatest percentage on tariff rates is attributed to cement, iron & steel, gas and refined oil, amounting to an average ad valorem tariff rate on imports of more than 15 per cent but less than 20 per cent.

By contrast, the average ad valorem export rebates imposed on exports amount to, generally 5 per cent-10 per cent for cement, iron & steel, other energy-intensive exports, oil, and refined oil. Other manufacturing, food, gas and coal exports amount to less than 5 per cent.

Aye, there’s the rub. Because there is no agreed global framework on carbon pricing – either the how or the how much.

Concerns arise with how these measures will interact with already existing climate policies.

For example, both the EU and Canada have schemes that permit free allocation. How to adequately price the import charges while simultaneously phasing out export rebates presents certain challenges. Additionally, the provision of an export rebate starts to question the second purpose of such BCAs, namely, to encourage GHG producers to lower their embedded emissions.

BCAs In Action

CBAM in the EU

On May 10, 2023, the EU Parliament and Council officially adopted the EU CBAM.6 The measure was entered into force on May 17, 2023. On August 17, 2023, the EU Commission adopted the implementing regulation, setting out the requirements for the purposes of the transitional phase which took effect on Oct. 1, 2023.7

The transitional phase of the CBAM is currently in effect, beginning on Oct. 1, 2023, and to last until Dec. 31, 2024. During this period, importers are not required to comply with the full requirements of the CBAM, only limited ones including reporting requirements, with respect to both direct and indirect emissions embedded in their imports. Initially, the CBAM is to place a cost on imports of certain goods and certain carbon-intensive production including, cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen.8 During this period, importers may choose to import in one of three ways.

- Full reporting according to EU methodology.

- Reporting according to equivalent methods.

- Reporting according to default reference values.

Reporting according to default reference values is only applicable up until July 2024. As of Jan. 1, 2025, only reporting according to the EU methodology will be accepted.

In the definitive phase, the CBAM is designed to reflect the ETS. As of 2026, both EU domestic producers and EU importers will bear similar costs for the embedded emissions of their imported goods. EU domestic producers will pay the CO2 price of their emissions while simultaneously surrendering their previously used free allocations under the ETS. By 2030, the EU CBAM is intended to be extended to all products currently subject to the ETS.9

EU importers of goods under CBAM will be required to purchase CBAM certificates calculated according to the weekly average auction price of EU ETC allowances per tonne of CO2. Upon importation, EU importers will declare their emissions and surrender their CBAM certificates proportionate to the embedded emissions.

There is one exception select importers may benefit from. If importers can provide that they are already subject to a carbon pricing scheme in their domestic country when they produce the imported goods, the difference in price may be deducted.10 How this will roll-out in practice presents further concerns with adequately pricing the direct vs. indirect embedded emissions associated with the imported goods.

How Canada is directly impacted by the EU CBAM

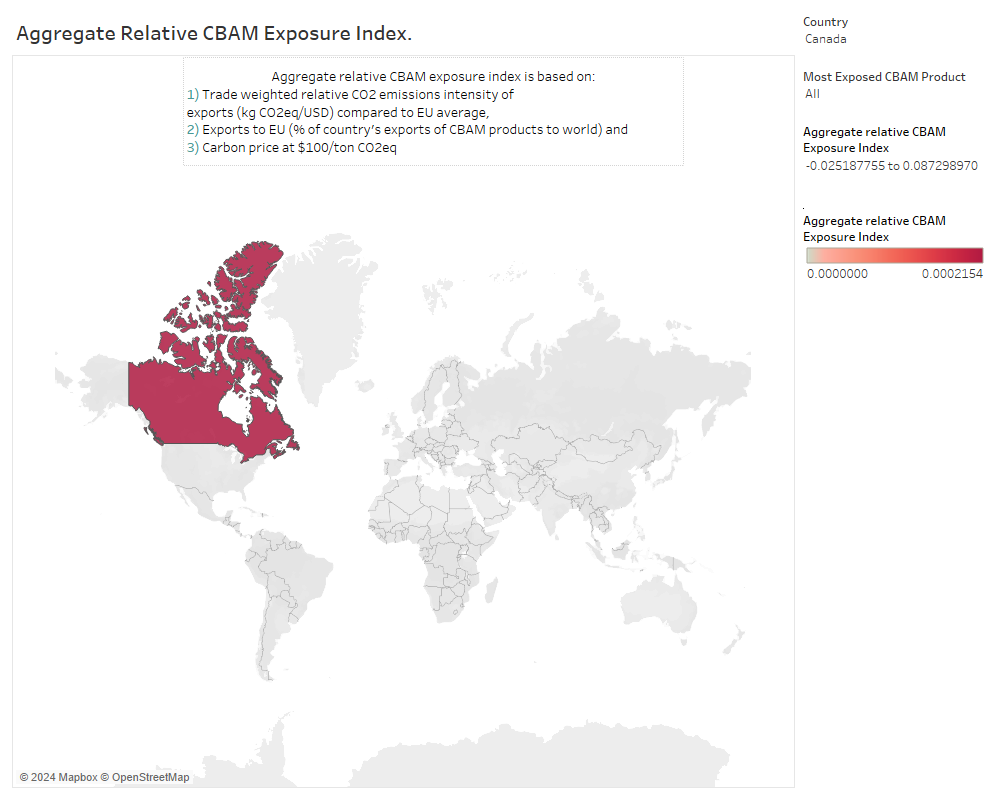

More than 70 per cent of Canada’s exports are either a variety of fossil fuels or goods resulting from EITE sectors. Canada’s most CBAM-exposed exports are iron and steel. Canada’s aggregate CBAM exposure remains relatively low.11

(source: World Bank < Relative CBAM Exposure Index (worldbank.org)>)

Given composition of Canada’s exports, and particularly the high per cent of EITE goods, CBAM could have a very significant impact on our competitiveness should it impose additional costs on exports the EU. Given this potential impact, the imperative for Canada should be taking steps to ensure that the potential impact of CBAM and BCAs generally is mitigated through domestic policy that allows us to control policy to the greatest extent. Otherwise, we could find ourselves along for the ride.

Global Response

While the CBAM is not without its controversy, no one seems to be objecting to the actual principle behind BCAs as measures to achieve both targeted climate goals and a level playing field (through leakage avoidance).

There is, inevitably, a chasm between BCAs in conception and the measures required for the implementation, administration, and enforcement of CBAM as a mechanism. There seems to be differing perspectives with respect to the implementation of CBAM and like measures.

Countries Implementing BCAs

Countries are following suit and implementing similar measures. For example, Turkey, Vietnam and Thailand have stated their intentions to create measures that mimic the EU CBAM. Similarly, the United Kingdom has proposed a CBAM to enter into force in 2027. The UK CBAM closely mirrors its EU counterpart.

The Government of Canada first indicated its intention in the 2020 Fall Economic Statement of its plans to explore a BCA. More recently in its 2021 Budget it reiterated those plans and subsequently held public consultations in the fall of 2021.

In an attempt to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030, other countries are proposing measures to reduce emissions. The United States has various pieces of legislation in draft, including the Clean Competition Act (CCA), the Fair, Affordable, Innovative, and Resilient Transition and Competition Act (FAIR Act), and the Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA). These measures share a similar goal in reducing the competitive advantage domestic industries experience in contrast to imported producers while taking direct steps to reduce GHG emissions.12

Countries Expressing Concerns

At the same time, the implementation and roll-out of the CBAM has not been without controversy.

For example, China has expressed concerns of the legality of such measures under the WTO Agreement. Other Chinese experts have revived the North-South dialogue, arguing that the CBAM is generally widely supported by developed countries, represented by the Group of Seven (G7), or rather, adopt an open attitude towards these measures, while developing countries generally oppose or are apprehensive towards such measures given their contribution to global emission levels.13

Moving Forward

The implications are significant no matter the option chosen.

What it means for Canada

Goods from EITE sectors14 generally account for more than 70 per cent of Canada’s exports.15 Canada’s largest export destination for EITE goods include the United States, followed by the United Kingdom, the EU, and China. If the US follow suits with the EU and the UK and begins implementing BCAs/ CBAMs to their climate policies, then over 80 per cent of Canada’s estimated exports of EITE produced goods will be subject to a carbon pricing scheme abroad upon importation.

Canada does not operate in a vacuum. We are very trade exposed and domestic policy is the only tool in our control to ensure our exports are not subject to BCAs.

The federal backstop may alleviate some of the costs faced, however, the roll-out of such plans remains uncertain.

Ultimately, if Canada’s trading partners proceed with levying EITE sectors, this could negatively affect Canadian industries. A home-made carbon pricing framework may, in turn, be the most effective mechanism to forestall or off-set all or at least most of the carbon costs associated with exports.

Exports are greater for certain EITE sectors, such as oil & gas where exports are greater than imports. The reverse is true for other sectors, such as Motor Vehicle and Parts. Thus, this could have an effect in off-setting some of the carbon costs associated with EITE sectors.